Cornwall Climate Catch Ups: Matt Slater

Marine Conservation Officer at Cornwall Wildlife Trust

It was a pleasure to be interviewed a few years ago for the Cornwall Climate Care film ‘Plenty more Fish’? – a film highlighting the ever-changing nature of marine life in our waters.

Since the film was made, we have seen continued shifts – with warm water species doing well and cool water species faring far less well around our coasts.

Pacific oysters have continued to colonise our estuaries and bays and we are rapidly realising that controlling them is going to be exceedingly difficult, while eradication is impossible. In certain important areas such as harbours, where oysters growing on infrastructure such as docksides and slipways constitutes a hazard to operations and safety, the manual control of oysters is feasible, but overall control of oysters in our waters is something that is now too large a problem to tackle. In 2022 DEFRA announced that Pacific oysters are “currently considered to be established in England south of latitude 52°N and therefore, with current technology, cannot be prevented from establishing in, or be successfully or economically eradicated from, this area.’

This means that we have been told by the government we will have to learn to live with them. A similar situation was declared on French shores two decades ago and the widespread settlement of oysters we have witnessed here is most likely due to larvae drifting over the channel from French oyster beds.

On a positive note, despite initial concerns of the oyster reefs overwhelming mud banks in our marine protected areas, it seems that this process is not occurring at the rapid rate that was feared and there is little evidence that proliferation of oysters on rocky reefs has a negative impact on marine life. The oysters themselves are filtering sea water and with water quality continuing to be a major problem in Cornish waters there is an argument that oysters may end up playing an important role in improving environmental conditions in the long term.

Marine food chains are continuing to change and our mild winters and warmer summers with high rainfall events and large amounts of nutrients entering coastal waters via our rivers and estuaries is fueling high productivity in our seas. Sardines are thriving and this has attracted large predators such as humpback whales and Atlantic bluefin tuna, both of which are seen far more frequently than a decade ago. Seasearch divers and snorkelers witnessed a huge influx of juvenile red sea bream in the summer of 2024. This is a species that hasn’t been seen in large numbers since the 1980s and could become an important fishery species in the years to come.

Cod, haddock and pollack are all cool water species and they are continuing to fare poorly in our warming seas. Sadly, brown crabs (Cancer Pagurus) are another species that is not doing well. Many think this is a combination of warming seas and lack of management of the pot fishery that has proliferated in the past fifty years with no control whatsoever on fishing effort. Fishers’ fears that crabs are in trouble have hardly improved this year with the latest surprise change in our waters…

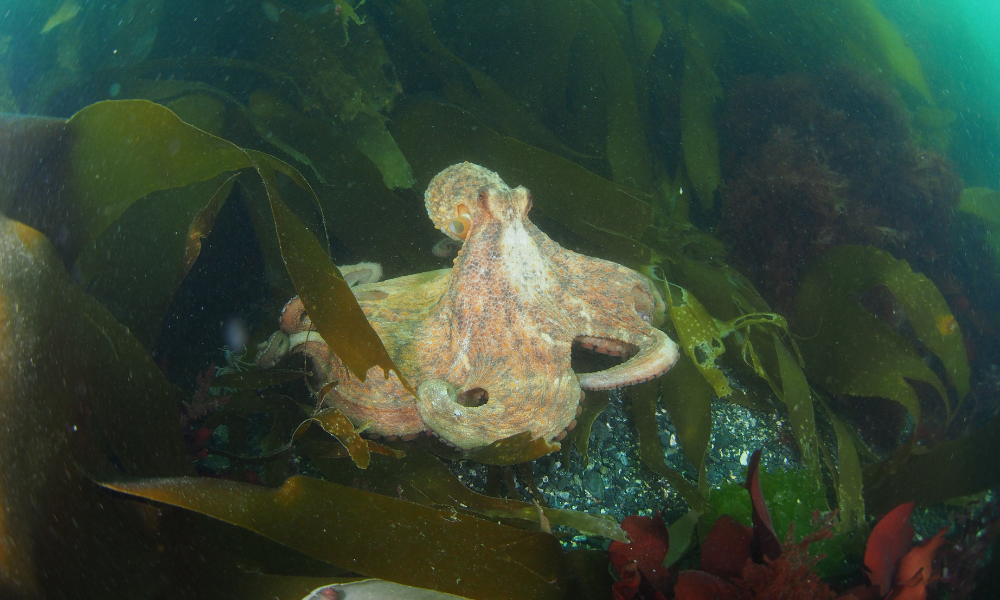

In spring 2025 a huge influx of common octopus appeared in our coastal waters along the south coasts of Cornwall and Devon. Fishers were finding them in crab and lobster pots in huge numbers (they love eating shellfish, crabs, lobsters and scallops) and trawlers began bringing them in from further offshore in large numbers. The octopus bloom of 2025 has been the largest seen in our waters since 1950. It is a natural phenomenon that occurs every 50 years or so but, as with previous blooms, fishers were extremely worried about the future of lobster and crab populations. A Mylor fisherman told me that in the peak of the bloom in June 2025, a fisher working in Falmouth Bay with 100 lobster pots could expect to land 3 tonnes of octopus per week! Divers and snorkelers (including our Seasearch volunteers) have been delighted to have seen such a fascinating creature in our waters, and a good price for octopus has been a consolation for some fishers who have landed large quantities.

The question ‘will we see more octopus blooms like this one?’ is being investigated by a team of researchers at the Marine Biological Association, and we are looking forward to the results of this research. Certainly, warming seas favour the growth and success of octopus larvae, and a decline in cod and other cold-water fish may have removed some of the predation pressure that would naturally keep octopus populations in check. Octopus larvae drift in the plankton for up to 2 months, during which time they need to find plenty of the right types of plankton to eat. They have very specific nutritional demands, and their success depends on multiple factors coming together – something that is far from guaranteed and which creates a natural boom and bust cycle. The frequency of the booms may be changing but we will have to wait and see if we will get more like this one!

One thing for sure is that things are going to continue to change in our waters. To ensure that we have a profitable and sustainable fishing industry we need to accept that improving management of fisheries has never been more important.

Spatial management of our seas is a way to effectively buy an insurance policy for fishers as well as allowing the restoration of our marine habitats. Well managed marine protected areas are an essential part of that management. I hope our government realises the importance of marine management and we see properly thought-out and enforced plans that allow our seas to adapt to changing conditions, ensuring both productive marine ecosystems and profitable, sustainable fisheries.